Home » Jura Soyfer

Category Archives: Jura Soyfer

The survival of the smuggled scripts

Under the Austrofascist regime established by Austria’s ultra-right-wing Fatherland Front Party in 1934 and lasting until the German annexation in 1938, small unofficial theatres were one of the few public arenas in which criticism of the regime and the growing influence of Nazi Germany could be voiced from within Austria. Large theatres with auditoriums for more than 50 people were strictly regulated through a system of licensing, which compelled managers and artists to comply strictly with the regime’s cultural policy and present an uncritical view of social and political events.1

However, those theatre workers prepared to make do with simple, low-budget productions on makeshift stages with audiences of less than 50 could avoid the heaviest penalties imposed by the censor and perform plays by writers critical of events in Nazi Germany and Austria. Such theatres included the avant-garde ‘Theater für 49’, where Hannah Norbert-Miller performed in the expressionist play ‘Das Leben des Menschen’ in the spring of 1937, as well as the political cabaret theatre, ABC Regenbogen Café, where Jura Soyfer was the in-house author.2

Miller 3/4/1/6 Feodor Weingart and Hanne Norbert in Das Leben des Menschen at the Theater für 49 in Vienna, April 1937

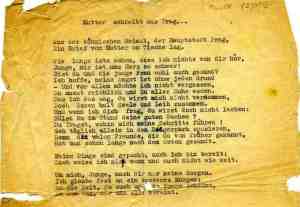

Unfortunately many of the records from this fascinating aspect of Austrian theatre history have gone missing without a trace.3 This is particularly true for the political cabaret scripts, which, given the political circumstances of their creation and the fact that they were written for immediate performance, were rarely published or made more broadly available. In the case of the highly political scripts of Jura Soyfer, many were confiscated and lost for good when he was arrested in November 1937. Under National Socialism, moreover, the possession of his work was a great risk, and some of the records of his writing were burnt by his parents and friends out of fear.4 Consequently only fragments of some of his work from this time have survived. For example, much of Soyfer’s novel, So starb einer Partei, which was the work he most valued, was lost. The image below shows a leaf from one of the surviving bundles of typescripts which found their way into the Millers’ possessions.

Miller 1/2/4/2. Page from surviving fragment of Jura Soyfer’s novel, So starb einer Partei

So how did his writing survive and his theatre plays end up being performed in London less than a year after his death in Buchenwald? Above all, it was because some of his friends, family and colleagues bravely risked their lives to carry the manuscripts beyond Austria’s borders. Otto Tausig, the leader of the exile theatre company, the ‘Austrian Youth Players’, later wrote that in the suitcases of some of those who emigrated after 1938, handwritten poems, a newspaper article or an almost complete play could lie hidden between the shirts or books.5

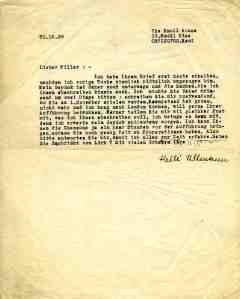

One of those courageous people who transported them was Helli Ultmann, Soyfer’s girlfriend. Ultmann made her way to exile in the USA via Paris and London, where she was in touch with Martin Miller and met him to pass on copies of Soyfer’s work. The letter below in the Miller Archive written by her in October 1939 to Martin Miller captures the moment when she arranged to pass on the smuggled material to Martin for the Laterndl:

Miller 2/126. Letter from Helli Ultmann to Martin Miller, October 1939. By kind permission of Monica Andis, daughter of Helli Andis (née Ultmann).

Roughly translated, the letter reads:

I can come to London, I would very much like to attend your performance. Also let me know by return of post what I should copy down for you, I will then bring it with me, as I’m expecting my luggage to arrive tomorrow at the latest. I can actually bring you the chansons a few hours before the performance, so you’ll still have enough time to prepare them.

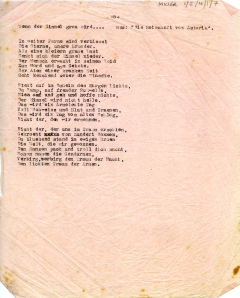

In all, two of Soyfer’s theatre scripts and seven of his song lyrics (such as the one below) ended up in the Miller collection. We cannot be sure which of the lyrics are the chansons referred to Ultmann in her letter, but for me the letter wonderfully captures a moment of triumph against Nazi oppression: when the bravery of those determined keep alive the memory of Soyfer and his political message won a small victory with the knowledge that his work would again be performed and celebrated in public.

Miller 1/2/4/1/7. Script of ‘Wenn der Himmel grau wird’ by Jura Soyfer

Footnotes

1 Barbara Nowotny, ‘Theater im Souterrain: Das politische Wiener Theater der 1. Republik’ (unpublished master’s thesis, University of Vienna, 2010), p28.

2 Viktoria Hertling, ‘Theater für 49: Ein vergessenes Avantgarde-Theater in Wien (1934-1938)’, in Jura Soyfer and his time, ed. by Donald G. Daviau (California: Ariadne Press, 1995), pp. 321-335.

3 Nowotny, p. 5. Hans Weigel also discusses this issue at multiple points in his book Gerichtstag vor 49 Leuten (Austria: Verlag Styria, 1981), for example, p. 33, p. 120 and p. 159.

4 Horst Jarka, Jura Soyfer: Leben, Werk, Zeit (Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 1987), p.498.

5 Jura Soyfer, Vom Paradies zum Weltuntergang, ed. by Otto Tausig (Vienna: Globus Verlag, 1947), p. 9.

Soyfer’s ‘Dachaulied’ (‘Dachau Song’)

In this post I want to look at how the poem composed by Jura Soyfer whilst he was in Dachau Concentration Camp in 1938, the ‘Dachaulied’, became known in the UK. As discussed in a previous post, the song was an ironic response to the Dachau Camp slogan: ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ (‘Work Makes you Free’).

This song is of particular interest to me as an archivist because its origins highlight the fact that not all of Soyfer’s lyrics and writing reached the outside world as written texts. In Dachau the poem could not actually be written down, of course, so knowledge of the lyrics had to be passed on orally. Once it had been set to music by the composer Herbert Zipper, who was in Dachau with Soyfer, and the song was recited to a small circle of Soyfer’s comrades, who memorised them and sang them in secret.1

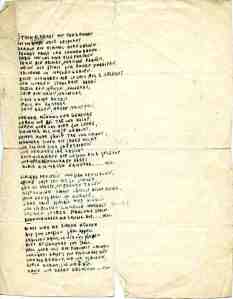

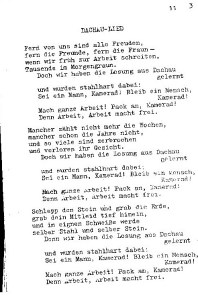

Miller 1/2/4/1/2. The ‘Dachaulied’ by Jura Sofyer, c. 1939.

A written record of the song was made only after Zipper had been released from Dachau and was safely in exile in Paris in March 1939. From Paris the song was brought by another Dachau inmate to the UK, where it circulated among the Austrian exile community. The image above shows what may be one of the first written records of the song. It is a rather tatty leaf manuscript, without a title or author and with a number of corrections and discrepancies with the (later?) published version. Possibly it was even written down from memory by someone who had been in Dachau with Soyfer.

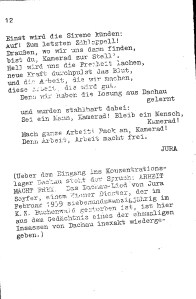

In London, the exiles did their best to promote the poem to the outside world. The youth exile group, Young Austria, were the first to publish the poem – it appeared in their journal Young Austria in November 1939.2 In 1940 it was published by so-called ‘enemy alien’ prisoners in Mooragh Internment Camp in Ramsey on the Isle of Man in their publication, Stimmen hinter Stacheldraht (Voices behind barbed wire). In the copy of the publication in the Exile Collection of the Germanic Studies Library archives shown above, the addendum below the poem translates as follows:

Above the entrance to Dachau Concentration Camp stands the slogan ‘Arbeit macht frei’. The ‘Dachau Song’ by Jura Soyfer, a Viennese poet who died aged 27 in Buchenwald in February 1939, is reproduced here inexactly from the memory of one of the former inmates of Dachau.

In 1942 the poem was also was published by the Austrian Centre again as one of the five Soyfer poems in the anthology Zwischen Gestern und Morgen, mentioned in a previous blog.

EXS.1.MIC. Jura Soyfer’s ‘Dachaulied’ in Stimmen hinter Stacheldraht (Voices behind Barbed Wire), a publication by ‘enemy aliens’ interned at Mooragh Internment Camp, Isle of Man, October 1940 (page 1)

EXS.1.MIC. Jura Soyfer’s ‘Dachaulied’ in Stimmen hinter Stacheldraht (Voices behind Barbed Wire), a publication by ‘enemy aliens’ interned at Mooragh Internment Camp, Isle of Man, October 1940 (page 2)

In the same year the ‘Dachaulied’ was then brought to the attention of officials in the Ministry of Information, probably by the Hungarian exile, Arthur Koestler, who had been employed to write propaganda film scripts for the Ministry. He incorporated the ‘Dachaulied’ into the film, Lift your Head, Comrade, which told the story of German and Austrian anti-fascist volunteers who had joined the British Army Pioneer Corps.3

Listen to this song. It is sung to this very day by the prisoners in the concentration camp at Dachau. It was written by a young Austrian poet in the camp, whom the SS men eventually killed. ‘Pitiless the barbed wired. All around is charged with death. Keep your step, comrade. Lift you head, comrade. And always think to the day, comrade, when the bells of freedom will ring.’

In the film the song has taken on the role of a battle song – exactly as Soyfer had intended. The film is available to view on the Imperial War Museum’s website here.

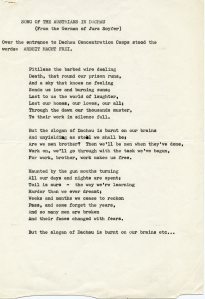

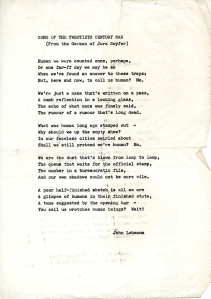

Miller 1/2/4/1/2 . ‘Song of the Austrians in Dachau’ by Soyfer, translated by John Lehmann, c. 1941

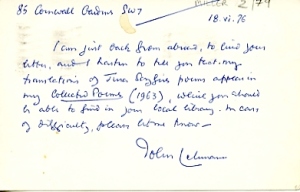

After the war the ‘Dachaulied’ became still better known to English speakers through the translations of John Lehmann. The above image is a typescript of Lehmann’s translation of the ‘Dachaulied’ in the Miller Archive, which he published in 1946 under the title ‘Song of the Austrians in Dachau’ in Poems from New Writing under the pseudonym Georg Anders. Lehmann was a great friend and admirer of Soyfer, writing in 1939 that Yura[sic] Soyfer, who ‘died in a Nazi concentration camp early this year’ was ‘a talented young Austrian writer, a Schutzbündler, who […] was one of the favourite writers of the little Viennese cabarets’.4 Lehmann was in fact responsible for publishing the only part of Soyfer’s novel to be published while Soyfer was still alive (in the first volume of his New Writing series in 1936). As the postcard below shows, he continued to promote Soyfer’s work over several decades, publishing more of Soyfer’s work in 1963.

Miller 2/79. Postcard from John Lehmann to Hannah Norbert-Miller, June 1976

Footnotes

1 Horst Jarka, Jura Soyfer: Leben, Werk, Zeit, (Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 1987), pp. 475-480.

2 Jennifer Taylor, ‘The Press of the Austrian Centre’ Out of Austria: the Austrian Centre in London in World War II, ed. by Marietta Bearman and others (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2008), pp. 59-85 (p. 77).

3 Matthew Lee, ‘The Ministry of Information and anti-fascist short films of the Second World War’, in Holocaust and the moving image: representations in film and television since 1933 (Great Britain: Wallflower Press, 2005), pp. 107-108.

4 John Lehmann, ‘About the contributors’, in New Writing, ed. by John Lehman (London: Hogarth Press, 1940), pp. 8-10 (p. 10). A Schutzbündler was a member of the paramilitary wing of the Austrian Social Democratic Party, the Republikanischer Schutzbund, which fought against the establishment of the authoritarian corporate state by Engelbert Dollfuss in 1933-34.

Commemorating Jura Soyfer

Last month marked the 75th anniversary of the death of the young Austrian cabaret writer, Jura Soyfer, in Buchenwald in February 1939. This is the first of a short series of blog posts aiming to show how actors at the Austrian exile theatre in London, the Laterndl, devastated by the news of Soyfer’s death, commemorated Soyfer with performances of his songs and plays. The posts will also highlight the importance of the collection for holding early records of Soyfer’s work.

Miller 6/1/1. Newspaper review of the cabaret production, Von Bagdad nach Vineta, at Vienna’s ABC cabaret theatre, autumn 1937 (original source unknown)

A number of the leading actors in the exile theatres, including Martin Miller, Rudolf Spitz, Jaro Klüger and Peter Preses, had worked with Soyfer in Vienna in the 1930s during the period of Austrofascist rule before the German annexation of March 1938. Soyfer had been the main writer behind the cabaret production at Vienna’s ABC Regenbogen Café, Von Bagdad nach Vineta (From Baghdad to Vineta) (reviewed in the above newspaper article), in which Martin Miller had performed (for more information see a previous post). The names ‘Fritz Feder’ and ‘Norbert Noll’ used in the article were in fact Soyfer’s pseudonyms.

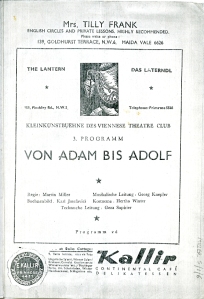

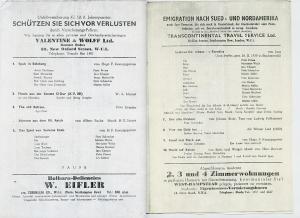

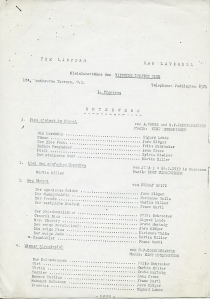

Miller 5/1/2. Programme (copy) for the Laterndl’s first show, Unterwegs

The Laterndl’s dedication to performing Soyfer’s work began with their first cabaret production, a programme for which is shown above. Unterwegs played from June until August 1939 under Martin Miller’s direction at the Austrian Centre near Paddington. Alongside the items by exile writers like Hugo F. Königsgarten and Rudolf Spitz, the programme lists Soyfer’s ‘Lied des einfachen Menschen’ (literally, ‘Song of the simple people’), sung by Martin Miller with Kurt Manschinger on the piano.

Miller 1/2/41/4. Script of ‘Lied des einfachen Menschen’ by Jura Soyfer

With his ‘Lied des einfachen Menschen’ Soyfer lamented the degrading and dehumanising effects of unemployment, which was rife in 1930s Austria. It is the only text to have survived from his play Pinguine. Ein Polarnachsttraum (Penguins. A polar night’s dream), first staged in Vienna in 1936, again with Martin Miller in the cast.1 The following recollection by Franz Bönsch, one of the Laterndl’s founding members, describes the effect of the performance on of the song on the exile audience:

In the Laterndl people cried together and laughed together. Unforgettable were the sobs which emanated from the audience […] when Jura Soyfer’s song was heard. ‘We are the name on the passport, we are the echo of what once was finely said, the rumour of a rumour that’s long dead’ – and there was something like a deep exhalation of breath as the song continued: ‘A poor, half-finished sketch is all we are, a glimpse of humans in their final state. A tune suggested by the opening bar. Your call us wretches human beings? Wait!’ 2

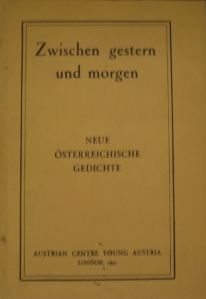

Front cover of Young Austria’s Zwischen Gestern und Morgen (London: Austrian Centre, 1942)

‘Ein einfacher Mann spricht’ (‘A simple man speaks’) was published by the Austrian exile group, Young Austria, in Zwischen Gestern und Morgen in 1942. It was just one of five poems by Sofyer published by the group, an indication of Soyfer’s significance for the exiled Austrian youth groups in London. It was also translated into English by John Lehmann, who had spent time with Soyfer in Vienna in the 1930s, and who later published the translation with the title ‘Song of the Twentieth-Century Man’ in his Collected Poems 1930-1963 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1963).

Miller 1/2/4/1/4. English translation by John Lehmann of Sofyer’s ‘Lied des einfachen Menschen’

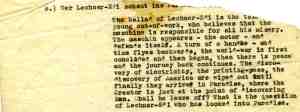

The Laterndl opened in its new home at 153 Finchley Road at the beginning of January 1940. The company then dedicated four full evenings (15, 22, 29 January and 5 February) to staging Soyfer’s work, marking the passing of nearly a year since Soyfer’s death on 16 February 1939. Again production and direction was led by Martin Miller. Two of the plays performed on these evenings were the two central pieces staged in Vienna in autumn 1937 mentioned in the review above: Vineta, die versunkene Stadt (Vineta, the sunken city) and Der treueste Bürger Bagdads: Ein orientalisches Märchen (The most faithful citizen of Baghdad: an oriental fable). The script of the latter (below), a short, one-act play which was bitingly satirical about the antisemitism of the Austrian authorities, a point which the Viennese newspaper reviews had all ignored.3 A third play staged as part of this tribute to Soyfer, Der Lechner Edi schaut ins Paradies, will be the focus of my next post.

Miller 1/2/4/3/2. Typescript of Soyfer’s Der treuste Bürger Bagdads

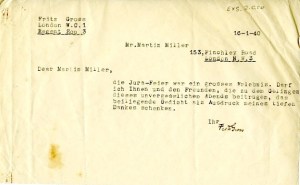

The reaction of the exile audience members to the production is illustrated by the letter below written to Martin Miller from another exile writer one day after the first performance. Fritz Gross wrote that ‘the Jura celebration was a great experience. May I present to you and the friends who contributed to the success of this unforgettable evening the enclosed poem as an expression of my deepest thanks’. Enclosed with the letter was a poem of nine stanzas, inscribed ‘Für Martin Miller. 16.1.40. Fritz Gross’.

EXS.2.GRO.2. Letter from Fritz Gross to Martin Miller concerning the commemoration of Jura Soyfer, 16 January 1940

Finally, I showed an extract from the speech below, ‘Jura Soyfer: eine Würdigung’ (‘Jura Soyfer: an appreciation’) in a previous post. I did not know at the time who wrote it or when it was given, but I have since discovered that it was written and presented by another Laterndl writer, Albert Fuchs, on the first anniversary of Jura Soyfer’s death.4 The speech has been described as the first attempt to set out Soyfer’s wider significance as a political writer rather than solely as a writer of cabaret sketches.5 As the most gifted Austrian writer of his generation and a great literary hope for the future, Soyfer would, according to Fuchs, have become the Austrian socialist poet.

Miller 1/2/1/6. Typescript of ‘Jura Soyfer: eine Würdigung’ by Albert Fuchs, 1940

Footnotes

1 This is not to say that this is the only copy of the song. For information about further copies please contact the Jura Soyfer Archive.

2 Franz Bönsch, ‘Das österreichische Exiltheater ‘Laterndl’ in London’, in Österreicher im Exil 1934 bis 1945: Protokoll des Internationalen Symposiums zur Erforschung des österreichischen Exils von 1934 bis 1945, ed. by Helene Maimann and Heinz Linzer (Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1977), pp. 440-450 (p. 447.

3 Horst Jarka, Jura Soyfer: Leben, Werk, Zeit (Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 1987), p. 343. The quotation from Soyfer’s song is the translation by John Lehmann mentioned later in the post.

4 Another typescript of the speech is in the Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes in Vienna.

5 Jarka, p. 502.

Remembering and resisting through poetry

Amongst the many scripts and song lyrics in the Miller collection there are a number of poems that relate to the theme of the Holocaust. Some of them were probably recited publicly by one of the exile theatre groups to draw attention to what was happening in their home countries. Others may have been kept simply for private reading by the Millers.

In some cases, as with the following poem, ‘Mother writes from Prague’, the author is unknown. In it, a mother writes a letter to her son from Prague, in the ‘Bohemian homeland’. She has not heard from him for a long time and his location is unknown to her. She expresses the usual motherly concerns – whether he is well, whether he is eating enough – as well as the hope that her fears about him are ungrounded. She says that her walks in Prague’s Rieger Park are now taken alone, as the many friends they had once known there have long been sent to the east – a euphemism for the ghettos and concentration camps. Though she doesn’t know when the time will come or how far she will have to go, she too, she says, has packed her bag and is prepared.

One small comfort against the sadness of this poem is the opening couple of lines which indicate that the letter has at least reached its intended recipient, the son: ‘a letter from Mother lay on the table’. The fact that she is writing from Prague to a son who appears to be in relative safety, suggests a parallel with Martin, some of whose family may have been living in what was by then the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. It is possible that the poem was written by one of the refugees in London, although this is by no means certain. I would be very grateful if any readers were able to provide any further information about the poem.

One writer represented in the collection with a strong association with the Holocaust is Jura Soyfer. Soyfer was a brilliant young journalist and writer of poetry, satirical plays for Vienna’s cabaret theatres, and a novel. He was also a Marxist and was active in the Vienna’s political underground in the 1930s. He was arrested even before the Nazi takeover of Austria, and was later released and re-arrested and sent to Dachau. After being transferred to Buchenwald he died of typhus in February 1939 aged just 26. His body was cremated in Weimar and his ashes, or what the Nazis claimed were his, were sent to his parents, who by this time had emigrated to the US.1

![By Hebrew Free Burial Association (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/jura_soyfers_gravesite_at_hebrew_free_burial_associations_mount_richmond_cemetery.jpg?w=300&h=225)

By Hebrew Free Burial Association (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Of the seven poems by Soyfer in the collection, the most well-known of these is his ‘Dachaulied’ (below). This, his last work, was composed whilst he was in Dachau Concentration Camp in 1938. The poem was set to music by another inmate and knowledge of the song spread from the camp inmates to the refugee circles in England and beyond.

The poem’s chorus revolves around the Nazi’s famous cynical slogan ‘Arbeit macht frei’, (‘work makes you free’), which was placed over the gates of many concentration camps. In Soyfer’s poem this reference becomes his call for resistance, which for Soyfer could only mean political engagement. The poem has been seen as an expression of belief in human dignity and hope, a belief which will outlive the catastrophe brought about by the Nazis.2

1 Horst Jarka, Jura Soyfer: Leben, Werk, Zeit (Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 1987), p.495.

2 Jura Soyfer, Das Gesamtwerk, ed. by Horst Jarka, 3 vols (Vienna: Europa Verlag, 1984), I: Lyrik, 26.