Home » Holocaust

Category Archives: Holocaust

Remembering and resisting through poetry

Amongst the many scripts and song lyrics in the Miller collection there are a number of poems that relate to the theme of the Holocaust. Some of them were probably recited publicly by one of the exile theatre groups to draw attention to what was happening in their home countries. Others may have been kept simply for private reading by the Millers.

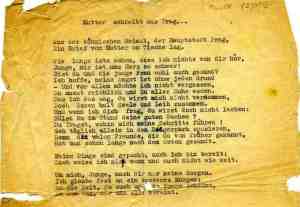

In some cases, as with the following poem, ‘Mother writes from Prague’, the author is unknown. In it, a mother writes a letter to her son from Prague, in the ‘Bohemian homeland’. She has not heard from him for a long time and his location is unknown to her. She expresses the usual motherly concerns – whether he is well, whether he is eating enough – as well as the hope that her fears about him are ungrounded. She says that her walks in Prague’s Rieger Park are now taken alone, as the many friends they had once known there have long been sent to the east – a euphemism for the ghettos and concentration camps. Though she doesn’t know when the time will come or how far she will have to go, she too, she says, has packed her bag and is prepared.

One small comfort against the sadness of this poem is the opening couple of lines which indicate that the letter has at least reached its intended recipient, the son: ‘a letter from Mother lay on the table’. The fact that she is writing from Prague to a son who appears to be in relative safety, suggests a parallel with Martin, some of whose family may have been living in what was by then the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. It is possible that the poem was written by one of the refugees in London, although this is by no means certain. I would be very grateful if any readers were able to provide any further information about the poem.

One writer represented in the collection with a strong association with the Holocaust is Jura Soyfer. Soyfer was a brilliant young journalist and writer of poetry, satirical plays for Vienna’s cabaret theatres, and a novel. He was also a Marxist and was active in the Vienna’s political underground in the 1930s. He was arrested even before the Nazi takeover of Austria, and was later released and re-arrested and sent to Dachau. After being transferred to Buchenwald he died of typhus in February 1939 aged just 26. His body was cremated in Weimar and his ashes, or what the Nazis claimed were his, were sent to his parents, who by this time had emigrated to the US.1

![By Hebrew Free Burial Association (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/jura_soyfers_gravesite_at_hebrew_free_burial_associations_mount_richmond_cemetery.jpg?w=300&h=225)

By Hebrew Free Burial Association (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

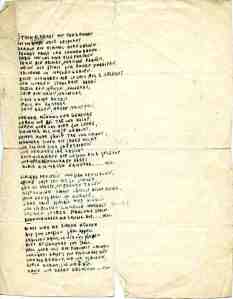

Of the seven poems by Soyfer in the collection, the most well-known of these is his ‘Dachaulied’ (below). This, his last work, was composed whilst he was in Dachau Concentration Camp in 1938. The poem was set to music by another inmate and knowledge of the song spread from the camp inmates to the refugee circles in England and beyond.

The poem’s chorus revolves around the Nazi’s famous cynical slogan ‘Arbeit macht frei’, (‘work makes you free’), which was placed over the gates of many concentration camps. In Soyfer’s poem this reference becomes his call for resistance, which for Soyfer could only mean political engagement. The poem has been seen as an expression of belief in human dignity and hope, a belief which will outlive the catastrophe brought about by the Nazis.2

1 Horst Jarka, Jura Soyfer: Leben, Werk, Zeit (Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 1987), p.495.

2 Jura Soyfer, Das Gesamtwerk, ed. by Horst Jarka, 3 vols (Vienna: Europa Verlag, 1984), I: Lyrik, 26.

Remembering family and friends

To mark Holocaust Remembrance Day last Sunday, this week I will post two blogs highlighting some of the papers in the collection which relate to the Nazi genocide, during which both Hannah and Martin lost family members.

Hannah explained what happened to members of her family who remained in Austria in an interview in 1995.1 At the age of 91, her grandfather (on her mother’s side) was taken to Theresienstadt where he later died. Hannah’s aunts and cousins on the same side of the family also disappeared. Hannah’s grandmother on her father’s side refused to leave Vienna with her son, saying that ‘nothing will happen to an old woman’. Despite her age (she was over 80), she too disappeared, together with her daughter, who had refused to leave her. When Hannah returned to Vienna in 1970, for the first time since 1939, it was a ‘completely strange town’, empty of all her former family or friends.

Although the details of Martin’s family’s fate are not as clear, there is some material in the collection which illuminates the life story of one of his relatives who remained in Vienna. By matching her personal details with data collected by the Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (DöW – the Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance), it has been possible to piece together what may have been her ultimate fate.

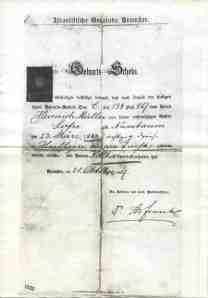

Katharina Müller was born on 23 March 1883 in Hullein (now Hulín in the Czech Republic), just six kilometers away from Kremsier (Kroměříž), in what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Martin too was born here, 16 years later in 1899, then Rudolf Müller.2 Unfortunately I do not know the exact relationship between Martin and Katharina.3

Katharina’s parents were Heinrich and Sofie Müller. As the copy of her birth certificate below shows, her birth was registered with the records of the Jewish Community of Kremsier. Note that the certificate itself is dated 21 October 1907, so it must have been created retrospectively.

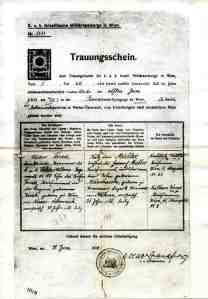

Katharina’s marriage certificate (also a copy) indicates that, in June 1918 at the age of 35, she married Victor Fried, a Landsturm-Kanonier (private in the reserve forces) of Field Artillery Regiment 157 of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The marriage was registered by the Imperial Jewish military pastoral ministry, and the wedding took place at a garrison synagogue in Vienna.

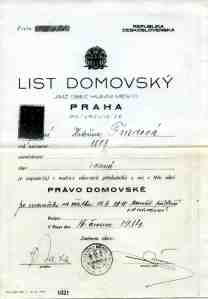

The next document relating to Katharina’s life shows that in July 1934 her main place of residence was Prague. The document below is a copy of the certificate of residence that was issued to her by the authorities of the Czechoslovak Republic, a state which was itself only to survive another four years. No details of her occupation are given, and she is described as ‘married’. Interestingly, the form does not require her nationality or religion to be given. Katharina would have been one of around 35,500 Jews living in Prague at this time.

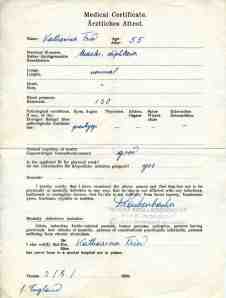

The final document on Katharina is a medical certificate dated 3 August 1939. By this time Katharina was back in Vienna, aged 55. The certificate is signed and stamped by a doctor who was only permitted to treat Jews. Katharina’s health was described as good and she was apparently fit for work. Presumably Katharina arranged to get a certificate in the hope that it would enable her to move to England. At the bottom of the certificate, the words ‘1. England’ are written.

Sadly, it appears that Katharina did not manage to escape to England. The records gathered by the DöW state that on 27 April 1942 a Katharina Fried, born 22 March 1883 in Hullein, was deported to the Jewish ghetto of a small Polish town near Lublin called Wlodawa. She may have died there or may have been one of the many who were transported from there to the extermination camp at Sobibor, only 11km away. Further details of what happened can be found here: http://www.doew.at/ausstellung/shoahopferdb_en.html. It is not known how her certificates were passed on to the Millers.

1 Archive of the Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies, University of London, Exile Archive, Interview with Hannah Norbert Miller by Charmian Brinson, December 1995.

2 Martin Miller was initially just a stage name.

3 Since writing this blog I have been told that Katharina was one of Martin’s older siblings. Thanks very much to Daniel Miller and to Anonymous who commented on this post for letting me know.