Home » Posts tagged 'Martin Miller' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: Martin Miller

Martin Miller’s sponsors

Until now relatively little was known about the two women who probably saved Martin Miller’s life by helping him to emigrate to the UK from Berlin in March 1939. There are no records of either his journey from Germany or the arrangements the women made to bring him to the UK. In an interview in 1995 Hannah Norbert-Miller reported that the women, a Miss Howson and Miss Townsend, were Quakers who had ‘already brought some refugees over and … wanted to bring people from all walks of life’.1 She also stated that the women lived in Putney and had bought another house nearby to house the refugees after their arrival.

Close examination of a number of items during the course of cataloguing, and a little background research have uncovered a few details which shed a little more light on the house and identity of the two women. Letters like this one, sent to Martin from Berlin just three weeks after his arrival in the UK, reveal the location of the house provided by the women for the refugees: it was at number 37, Deodar Road, a road running parallel to the Thames near Putney Bridge. Three months earlier than Martin, the South African writer, Pauline Smith, had also been a resident of the house and had described in a letter her view across the river and the wharf opposite, where boats bringing bricks from Holland and marble from Italy docked. She also wrote that she had met some of the Jewish refugees staying in the house and had tried to comfort them when ‘news of the sufferings of their people still in Germany reaches them’.2

More information about the women themselves was revealed when I came across a another letter sent from Deodar Road from 1955 (below). This time the house number was 79, but I guessed that the proximity of the two addresses was unlikely to be a coincidence and soon realised that it was written by one of the women who had sponsored Martin in 1939. The letter itself was just a message of thanks for a gift, but what caught my eye was the headed notepaper on which it was written. It revealed that the writer was in fact the British stained glass artist of the Arts and Crafts movement, Joan Howson.

Joan Howson (1885-1964) had studied textile design and stained glass at Liverpool School of Art before moving to London.3 There she became the first pupil and lifelong friend of Caroline Charlotte Townsend (1878–1944), another well-known stained glass artist, who was, of course, the second of Martin’s sponsors. From 1920 the women worked together in partnership at their house in Deodar Road, which they converted into a studio and workshop, and were neighbours to a number of Arts and Crafts stained glass artists.

![Dove Window in All Saints' Church, High Wycombe, designed by Townshend and Howson commemorating women's campaigner, Frances Dove. Photograph by Weglinde (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/dove.png?w=100&h=150)

Window in All Saints’, High Wycombe, designed by Townshend and Howson, commemorating women’s campaigner, Frances Dove. Photograph by Weglinde (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Howson and Townsend had much in common: as well as their professional partnership, both were involved in the suffragette movement and shared an interest in socialism. One of Townsend’s best-known works is the Fabian window at the London School of Economics, which was designed by George Bernard Shaw in 1910 in commemoration of the Society, and unveiled by Tony Blair in 2010 when it was recovered and installed after having been lost for more than 25 years. The window depicts a number of figures involved in progressive politics at the time, including Townshend herself and HG Wells. For more on this see http://www.lse.ac.uk/newsAndMedia/news/archives/2006/FabianWindow.aspx

Martin Miller was one of many refugees from Nazi Germany and Austria whom Howson and Townsend helped to escape to the safety of the UK and then supported. In each case they would have paid the required £50 per refugee as a guarantee that the person admitted would not be a burden on the British State, and then also provided accommodation for them when they arrived. Thousands of refugees’ lives were saved in this way by Quakers like Howson and Townsend. For more information see http://remember.org/unite/quakers.htm.

![Arrival of Jewish refugees, London, Feb 1939. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S69279 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/bundesarchiv_bild_183-s69279_london_ankunft_jc3bcdische_flc3bcchtlinge-1.jpg?w=150&h=105)

Arrival of Jewish refugees, London, Feb 1939. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S69279 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Martin’s original intention was to stay in the UK for just six months. This would, he hoped, give him enough time to learn English before moving to the US, where a relative had signed an affadavit of support for him. However, with the outbreak of war he decided to remain in the UK, where he had already established himself as a central figure in the Austrian exile theatre, the Laterndl. It may possibly have been through Martin’s friendship with Howson and Townsend that HG Wells came to be present at the Laterndl’s opening evening in June 1939.

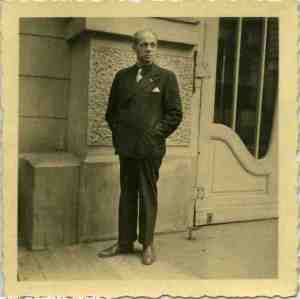

Unfortunately there is very little in the collection to testify to the connection between Martin and Townsend, who died in 1944. However, there is one photograph (above), of what appears to be a small group visit to a sculptor at work in his studio. The photo is inscribed on the reverse ‘David Linkmann from CC Townsend’. As yet I have been unable to find out any more information about David Linkmann or to identify anyone else in the photo (other than Martin, in the middle of the three visitors). I would be delighted to hear from anyone who might be able to enlighten me!

Footnotes

1 Archive of the Institute of Modern Languages Research, University of London, Exile Archive, Interview with Hannah Norbert Miller by Charmian Brinson, December 1995.

2 Pauline Smith, ‘Letters July 1927-June 1956’English in Africa 23/2 (1996), 5-84 (p.16-17).

3 M.E. Aldrich Rope, ‘Obituary of Joan Howson’, Journal of Stained Glass, 14/2 (1965), 110-113.

‘Keeping something alive in the very jaws of death’: Martin Miller and Berlin’s ghetto theatre

Whilst cataloguing correspondence in the collection recently, I came across some letters sent to Martin Miller which throw some light on when and why Martin left Austria after the Anschluss in March 1938. The letters reveal that, having been banned from working in ‘German’ theatres in Austria, Martin managed to get himself a job with the only theatre company left in German-occupied territory which would then employ Jews: the Jüdischer Kulturbund (KuBu). So, incredible as it now seems given the increasing level of violence against Jews at that time, in late October or early November 1938 Martin headed to the very heart of the Third Reich: Berlin.

The Jewish ghetto theatre run by the KuBu was located just twenty minutes’ walk from the government district, in the Kommandantenstraße in Kreuzberg, and it survived (though ever more precariously) until 1941. The KuBu itself was established after the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933, when Jewish artists and intellectuals were banned from working in the country’s cultural institutions. The director reported to the Ministry of Propaganda, which strictly controlled its work and membership. All Jews in the performing arts were required to join the KuBu, and Jews alone could join, attend and review events. Permission to put on certain plays was refused if they were deemed either ‘too assimilatory’ to German life (i.e. not Jewish enough) or, by contrast, were thought ‘too Jewish’.

Memorial plaque to the theatre of the Jüdische Kulturbund. By OTFW, Berlin (Self-photographed) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

The earliest letter in the collection from the KuBu indicates that Martin first wrote to the company from Vienna asking for work in early September 1938. Dr Werner Levie, one of the directors, responded that no decision could be made immediately because the acting and directing manager, Fritz Wisten, was then on holiday (a strikingly ordinary-sounding activity for a Jew in Berlin at that time). However, Levie’s comment that he had seen Martin perform in “Jud Süss” in Vienna in November 1937 (see a previous blog) probably raised Martin’s hopes, as his performance had been very well received by critics.

The second letter, dated 3 October (shown above), was from Wisten himself and stated that the KuBu would be delighted to welcome Martin as a member of the group, but was unfortunately unable to commit to doing so just then. In fact this letter coincided with a period of upheaval for the KuBu, as its managing and artistic director, Kurt Singer, was making plans to go on a six-week tour of America, partly to raise funds for the company. [Footnote: Rovit, p. 142] However, a short time later leadership of the company was settled, and with Levie as Acting Artistic Manager during Singer’s absence, Martin’s engagement was agreed. His contract ran from 1 November until 31 March 1939, during which time his wages were 250 RM per month and he was entitled to one week’s paid holiday.

Interior view of the destroyed Fasanenstrasse Synagogue, Berlin, burned on Kristallnacht; November Pogroms. Center for Jewish History, NYC [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Rehearsals for Martin’s first play with the KuBu, Benjamin … wohin? (Where to, Benjamin?) were interrupted by the Kristallnacht pogrom of 9-10 of November, when all KuBu activities were called to a halt and most Jewish males were summarily imprisoned . Exactly what happened to Martin is not certain, but Wisten and some of the other actors were detained in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, just north of Berlin. Wisten was released five days later with a shaven head and pneumonia, on the understanding that he would return to work at the theatre and would keep productions going, despite the low morale and depleted performer and audience numbers.1

As well as the correspondence there are also two KuBu programmes in the collection: the above is for Martin’s second play, Ferenc Molnar’s Die Fee (The Good Fairy), staged in January 1939. The list of actors illustrates a new Nazi requirement, just implemented, for all Jews to take ‘Israel’ or ‘Sara’ as their middle names. The programmes are also full of adverts for shipping companies offering Jewish would-be emigrants transport routes out of Europe.

Martin’s third and final part in a KuBu production was as King Leontes in Shakespeare’s Wintermärchen (or A Winter’s Tale). The play was probably chosen with the aim of amusing the audience whilst also ‘offering an allegorical story for solace during difficult times’.2 According to one review in the collection, Martin’s ‘stocky figure’ and ‘heavy head on a short neck’ was not very regal, but he made up for this with his ‘powerful kingly demeanor’ conveyed through his ‘astonishing vocal and physical range of action’, which gripped the spectators’ attention.3

A postcard in the collection dated 7 February 1939 from Wisten to Martin seems to suggest that in the short time that he was in Berlin, Martin became an important figure within the company on both a professional and a personal level. The postcard (which shows a portrait photo of Wisten on the front) reads: ‘My dear Miller, we met each other late, but the pleasure of working with you has made me forget the time lost. At the end of my artistic work for the KuBu is your Leontes! That is a lucky sign. Warm greetings, your Fritz Wisten’.

Certainly the experience of working there seems to have been of great personal significance to Martin himself: in an interview in 1967, when asked about his experiences in the KuBu, he responded as follows: ‘in a way, you know, I felt better in Germany itself. I felt I was keeping something alive in the very jaws of death; in Vienna, one felt almost frivolous playing in the theatre while the European world collapsed’.4

The end of Martin’s association with the KuBu is marked by a letter to him from Levie dated 28 March 1939, by which time Martin was safely in exile in the UK. Levie wrote that, despite Martin’s short time with the KuBu, he appeared to have fully grasped what the company was striving to do. He also expressed the hope that he would meet Martin again soon in London. In 1943 Levie was arrested in Holland, however, having led a similar cultural foundation to the KuBu there for two years. He died in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp in 1945.

Footnotes

1 Rebecca Rovit, The Jewish Kulturbund Theatre Company in Nazi Berlin (Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2012), p. 148.

2 Rovit, p. 153.

3 Julius Bab, ‘Jüdischer Schauspieler: Rudolf Müller’ in Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt, 17 February 1939, p. 9.

4 ‘Jewishness and the Theatre’, The Jewish Telegraph, c. 1967.

Life before emigration: Martin Miller in Vienna

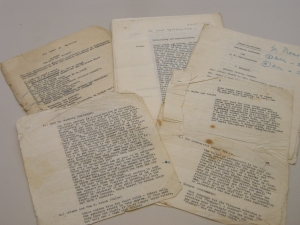

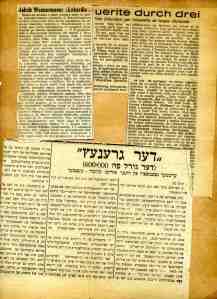

After leaving Reichenberg in 1931, Martin continued to tour theatres in Austria and beyond for a further three years. He was based at the Stadttheater in Aussig (by then, Ústí nad Labem in Czechoslovakia) from 1931 to 1933, at the Deutsches Theater in Mährisch-Ostrau (Ostrava, Czechoslovakia) from 1933 to 1935, and at the Theatre Municipale in Strasbourg from 1935 to 1936. The newspaper reviews in the collection of the productions in which he performed give some indication of the diverse linguistic communities to whom he was performing.

Shown above are: a Czech review of a production of Jakob Wassermann’s Lukardis in Mährisch-Ostrau in 1934, in which Martin played a Russian revolutionary; a French review of a production of Fritz Schweifert’s Marguerite durch drei in Strasbourg in 1935/36, in which he played one of the leading lady’s three deceived suitors; and a Yiddish review of a production of Die Grenze. Ein Schicksal unter 600.000 (The Border. One fate amongst 600,000), translated from Danish and adapted by Awrum Halbert (under the pseudonym Albert Ganzert), performed at the Jüdische Kulturtheater in Vienna in 1936. In this play, the Jüdische Kulturtheater’s most successful production, Martin played a respected businessman who provides a role model for his grandson when his Jewish background is exposed and he is hauled before the courts in Nazi Germany.1

Martin had maintained professional and family links with Vienna over the years that he worked away. From about 1935-1936 until his exile in 1938, he worked on a more steady basis in Vienna. By this time he was not just acting but also directing the plays he was in, for example at the Neues Theater in der Praterstrasse and the Theater der Schulen in der Volksoper. The image below shows some of the reviews he kept of the productions on which he worked at this time.

In 1936 Martin joined a small number of actors who performed regularly at the Jüdisches Kulturtheater in Vienna. The theatre had only just been established, and it employed mainly German Jewish actors in exile from Nazi Germany. It had one of the most politically active repetoires in Vienna at that time; its plays (like Die Grenze, mentioned above) often dealt with antisemitism and events in contemporary Germany.2 In 1937 Martin starred here again in another play focusing on anti-semitism: Ashley Dukes’ adaptation of Lion Feuchtwanger’s novel, Jüd Süß. The image below shows Martin Miller as Herzog Karl Alexander and Lisl Einberger as Naemie, the daughter of Josef Süss Oppenheimer. The caption reads ‘Naomi evading the hands of the Duke’; the first line is written in Yiddish and the second in Hebrew.3 The newspaper source is not known.

As well as acting in regular plays, Martin also organised events at which he performed as a solo artist reciting from poems or acting out characters from plays. Perhaps this allowed him to focus on the character portrayals for which he had become known. The invitation below is for just such an evening at the Jüdisches Kulturtheater on 23 May 1936, at which Martin read and acted out characterisations of a range of Jewish figures in literary sources from Shakespeare to the Austrian writer Arthur Schnitzler. The handwritten message from him reads ‘it would be nice if you were there!’; unfortunately it is not known to whom this is addressed. A review in the collection praised this exploration of Jewish suffering over 400 years, and suggested that Martin was one of the best character actors of Jews in Vienna.

Invitation to a recitation of ‘Judenrollen’ (Jewish roles) at the Jüdisches Kulturtheater from Martin Miller, c1936

As well as his work at the Jüdisches Kulturtheater, Martin now also began to perform in Vienna’s cabaret scene, which was rapidly becoming one of the few public spaces where political dissent could be expressed.4 Below is a review of a 1936 cabaret show in which Martin worked alongside Jura Soyfer, Friedrich Torberg and Peter Hammerschlag at the cabaret theatre, Literatur am Naschmarkt. The reviewer’s comments on Martin’s individual contribution roughly translate as

Martin brings forth a storm of laughter with his stunningly successful dramatic parodies of actors from Ferdinand Onno to Hans Moser, Alexander Moissi and Werner Krauß and to Max Pallenberg and Albert Bassermann.

The objects of Martin’s impressionist skills were all successful German or Austrian theatre actors in the 1930s, well-known at that time. Of those who had been based in Germany, all except the antisemitic Krauß had already left the country and gone into exile in Austria. Krauß, by contrast, had by this time had been honoured by the Nazis with the status of Staatsschauspieler (actor of national importance); he was soon to lend his acting skills to the Nazis by starring in one of the most antisemitic propaganda films ever made, Jud Süß. It can perhaps be expected, then, that he of all them came off worst from Martin’s cutting satirical impressionist talents.

From September to November 1937, Martin performed at the ABC Theater in the cabaret show ‘Von Bagadad nach Vineta’. The central pieces of the show were Jura Soyfer’s sketches Vineta, die versunkene Stadt and Der treuste Bürger Bagdads. However, Martin’s individual contribution was also very well received by the liberal critics (possibly from the liberal Wiener Tag) who reviewed the show: ‘eine erlesene Delikatesse ist ein Vortrag Martin Millers, der vollendet kleine Wortkunstwerte Polgars bringt’ (Martin Miller’s presentation, which perfectly conveys the aphorisms of [Austrian journalist Alfred] Polgar, is a choice delicacy of the show).

![The annexation of Austria - German troops in Vienna. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1985-083-10 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/german-troops-in-vienna-in-1938.jpg?w=300&h=206)

The annexation of Austria – German troops in Vienna. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1985-083-10 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Time was, of course, running out. Jura Soyfer, as mentioned in a previous post, had already been imprisoned in Dachau. Following the annexation of Austria in March 1938 Martin, as a Jew, was immediately forbidden to participate in the theatre. Cultural institutions in Vienna were were very quickly reorganised and ‘Aryanised’. On 11 March the Jüdisches Kulturtheater was looted and closed.5 According to Yates, ‘in the course of the summer of 1938 everyone working in the theatre had to provide documentary evidence of his or her ‘Aryan’ descent’.6 Eight months later, on 1 November 1938, Martin emigrated to Berlin.

Footnotes

1 Brigitte Dalinger, Verloschene Sterne: Geschichte des jüdischen Theaters in Wien (Vienna: Picus Verlag, 1998), p. 116.

2 Brigitte Dalinger, ‘Jiddisches Theater in Wien, Berlin und Prag’, in Berlin – Wien – Prag : Moderne, Minderheiten und Migration in der Zwischenkriegszeit. Modernity, minorities and migration in the inter-war period, ed. by Susanne Marten-Finnis and Matthias Uecker (Bern: Peter Lang, 2001), pp. 271-287 (p. 285).

3 Many thanks to Rachel Bracha, Archive Co-ordinator at Archive Coordinator, World ORT, for her translation of the caption for this photograph.

4 W.E. Yates, Theatre in Vienna: a Critical History 1776-1995 (Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 222.

5 Salzburg University, ‘Österreichische Schriftstellerinnen und Schriftsteller des Exils seit 1933’, http://www.literaturepochen.at/exil/lecture_5003_18.html, accessed 3 April 2013.

6 Dalinger, ‘Jiddisches Theater’, p. 224.

Remembering family and friends

To mark Holocaust Remembrance Day last Sunday, this week I will post two blogs highlighting some of the papers in the collection which relate to the Nazi genocide, during which both Hannah and Martin lost family members.

Hannah explained what happened to members of her family who remained in Austria in an interview in 1995.1 At the age of 91, her grandfather (on her mother’s side) was taken to Theresienstadt where he later died. Hannah’s aunts and cousins on the same side of the family also disappeared. Hannah’s grandmother on her father’s side refused to leave Vienna with her son, saying that ‘nothing will happen to an old woman’. Despite her age (she was over 80), she too disappeared, together with her daughter, who had refused to leave her. When Hannah returned to Vienna in 1970, for the first time since 1939, it was a ‘completely strange town’, empty of all her former family or friends.

Although the details of Martin’s family’s fate are not as clear, there is some material in the collection which illuminates the life story of one of his relatives who remained in Vienna. By matching her personal details with data collected by the Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (DöW – the Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance), it has been possible to piece together what may have been her ultimate fate.

Katharina Müller was born on 23 March 1883 in Hullein (now Hulín in the Czech Republic), just six kilometers away from Kremsier (Kroměříž), in what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Martin too was born here, 16 years later in 1899, then Rudolf Müller.2 Unfortunately I do not know the exact relationship between Martin and Katharina.3

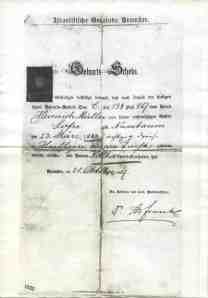

Katharina’s parents were Heinrich and Sofie Müller. As the copy of her birth certificate below shows, her birth was registered with the records of the Jewish Community of Kremsier. Note that the certificate itself is dated 21 October 1907, so it must have been created retrospectively.

Katharina’s marriage certificate (also a copy) indicates that, in June 1918 at the age of 35, she married Victor Fried, a Landsturm-Kanonier (private in the reserve forces) of Field Artillery Regiment 157 of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The marriage was registered by the Imperial Jewish military pastoral ministry, and the wedding took place at a garrison synagogue in Vienna.

The next document relating to Katharina’s life shows that in July 1934 her main place of residence was Prague. The document below is a copy of the certificate of residence that was issued to her by the authorities of the Czechoslovak Republic, a state which was itself only to survive another four years. No details of her occupation are given, and she is described as ‘married’. Interestingly, the form does not require her nationality or religion to be given. Katharina would have been one of around 35,500 Jews living in Prague at this time.

The final document on Katharina is a medical certificate dated 3 August 1939. By this time Katharina was back in Vienna, aged 55. The certificate is signed and stamped by a doctor who was only permitted to treat Jews. Katharina’s health was described as good and she was apparently fit for work. Presumably Katharina arranged to get a certificate in the hope that it would enable her to move to England. At the bottom of the certificate, the words ‘1. England’ are written.

Sadly, it appears that Katharina did not manage to escape to England. The records gathered by the DöW state that on 27 April 1942 a Katharina Fried, born 22 March 1883 in Hullein, was deported to the Jewish ghetto of a small Polish town near Lublin called Wlodawa. She may have died there or may have been one of the many who were transported from there to the extermination camp at Sobibor, only 11km away. Further details of what happened can be found here: http://www.doew.at/ausstellung/shoahopferdb_en.html. It is not known how her certificates were passed on to the Millers.

1 Archive of the Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies, University of London, Exile Archive, Interview with Hannah Norbert Miller by Charmian Brinson, December 1995.

2 Martin Miller was initially just a stage name.

3 Since writing this blog I have been told that Katharina was one of Martin’s older siblings. Thanks very much to Daniel Miller and to Anonymous who commented on this post for letting me know.

The Laterndl re-alights at 153 Finchley Road

Three months after the government’s enforced closure of theatres at the start of the Second World War, the rules were relaxed as it appeared there was no immediate danger of bombing raids. In January 1940 the Laterndl reopened in new and larger premises at 153 Finchley Road in Hampstead, north London. The company’s first production there was their second Kleinkunst revue-style show, Blinklichter (or Beacons), which was composed of sketches by Albert Fuchs, Karl Stefan, Rudolf Spitz and Peter Preses. One sketch in particular was to spread Martin Miller’s name far beyond the bounds of the Laterndl and its audiences. His impersonation of Hitler at the Laterndl in this show led to his invitation to broadcast the speech on BBC radio.1

It was at 153 Finchley Road that Hannah first became actively involved with the Laterndl. Until then, Hannah had only been to the Laterndl as an audience member and had only met Martin briefly whilst working on a play in Austria. She accepted the role of English language conférencier (the term for ‘master of ceremonies’ in European cabaret) for Blinklichter, a job for which Fritz Schrecker and Martin Miller had tracked her down specially, knowing that she spoke good English.2 She then went on to take her first acting role on a London stage in two of the sketches in the company’s third Kleinkunstprogramm: Von Adam bis Adolf in February 1940.

The Laterndl’s new premises also saw the start of a programme of organised evenings dedicated to particular writers who had taken a critical stand against the growing National Socialistst threat to Austria in the 1930s. A series of evenings was held for Jura Soyfer, for example, who was an Austrian Jewish socialist journalist who had written plays for the cabaret stage in Vienna in the 1930s. Soyfer was known personally to some of the Laterndl players, and after his death in Buchenwald in February 1939 they were determined to keep alive his memory through the staging and reading of his works. The three Welttheater shows performed in January 1940 were composed of his plays Der Lechner Edi schaut ins Paradies, Vineta, die versunkene Stadt and Der treueste Bürger Bagdads. For more information on Soyfer see http://www.soyfer.at/deutsch/auffuehrungen_1934-1945.htm.

The last show to be performed at 153 Finchley Road was Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper in May 1940, one of a number of a number of full-length dramas the company would produce as part of their Weltliteratur evenings. However, the players were now confronted with a problem facing all refugees from Germany and Austria in 1940: the internment of enemy aliens. Rehearsals saw the part of Mack the Knife played by three different male actors, as the first two actors were interned and had to be replaced. The loss of its main actors made it too difficult for the company to continue, and the Laterndl closed again, this time for 15 months.

Footnotes

1 Charmian Brinson and Richard Dove, ‘«Just about the best actor in England»: Martin Miller in London, 1939 bis 1945’, in Exilforschung: ein internationales Jahrbuch, ed. by Claus-Dieter Krohn (Munich: Text und Kritik, 1983- ), XXI: Film und Fotografie, ed. by Claus-Dieter Krohn and others (2003), pp. 129-140 (p. 130).

2 Archive of the Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies, University of London, Exile Archive, Interview with Hannah Norbert Miller by Charmian Brinson, December 1995.

The opening of the first Austrian exile theatre in London

Some of the most interesting items in this collection are the scripts, photographs, theatre programmes and press reviews that the Millers accumulated whilst working in exile theatre companies in London in the late 1930s and 1940s. This post gives a brief history of the opening of the main theatre company with which the Millers were associated, which was also the first German language exile theatre to be established in London: the Laterndl (or Lantern).

The Laterndl was founded by three Austrian refugees who wanted to keep alive the tradition of Viennese theatre and provide a home for Austrian drama and literature: Fritz Schrecker, Franz Schulz and Franz Hartl (a.k.a. Franz Bönsch). The latter, Franz Bönsch, later explained that they were driven by the desire to take part in the fight for an independent and free Austria. They also viewed the establishment of a German-speaking theatre as a way of relieving the uprooted and desperate exiles’ homesickness, giving them hope and a belief in the future.1

<img class="size-medium wp-image-289 " alt="Laterndl advert” src=”https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/laterndl-advert-1939.jpg?w=206″ width=”206″ height=”300″> Laterndl advert 1939The Laterndl‘s first performance took place on 21 June 1939 with the role of director undertaken by Martin, who had arrived in London in March of that year. In these early days of the company’s existence, its home was the Austrian Centre near Paddington, a self-help organisation set up by Austrian refugees to provide assistance and advice to other exiles. The photograph below is the only photograph I have come across which shows the interior of the rooms where the Laterndl performed at the Austrian Centre. In it you can see Martin with Grete Hartwig watching a rehearsal of the first Laterndl production, Unterwegs (On the Road), a revue-style composition of nine short sketches. The photo gives some idea of the limited space the company had in which to practise and perform: the auditorium held 60 to 70 seats, and the stage measured just five by three metres.2

<img class="size-medium wp-image-113 " alt="Laterndl rehearsal for Unterwegs at the Austrian Centre, 1939″ src=”https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/laterndl-rehearsal-for-unterwegs-at-the-austrian-centre-1939.jpg?w=300″ width=”300″ height=”244″> Laterndl rehearsal for Unterwegs at the Austrian Centre, 1939Unterwegs was typical of many of the Laterndl’s productions in the early years of its existence, when the group was heavily influenced by the Viennese version of cabaret known as Kleinkunstbühne. This was a politically-charged, often satirical form of revue theatre which had grown out of the politically and culturally repressive conditions of the Austrian capital in the mid- to late-1930s. The Laterndl’s Kleinkunst shows consisted of short plays and sketches written by members of the group which attempted to stoke political awareness of the situation in Austria and Germany.

<img class="size-medium wp-image-115 " alt="Cultural roots of the Laterndl 1939″ src=”https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/cultural-roots-of-the-laterndl-1939.jpg?w=209″ width=”209″ height=”300″> Cultural roots of the Laterndl 1939As the Laterndl’s published list of patrons and participants shows, the company was supported by influential figures in the British and Austrian cultural scenes from the beginning. It gained patronage from the playwright Ashley Dukes, the film actress Luise Rainer, the Times journalist Wickham Steed, and the London PEN Club (on which see http://www.exilpen.de/aboutus.html for more information). Amongst the visitors on its opening night were the Austrian writer and novelist Stefan Zweig, the Austrian parodist Robert Neumann, and the English authors H.G. Wells and J.B. Priestley.3

<img class="size-medium wp-image-114 " alt="Laterndl patrons and participants, 1939″ src=”https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/laterndl-patrons-and-participants-1939.jpg?w=213″ width=”213″ height=”300″> Laterndl patrons and participants, 1939Although the prime target was the German-speaking exile community, the comments below republished from the British press indicate that it was not only they who appreciated the contribution the Laterndl was to make to London’s wartime cultural life.

<img class="size-medium wp-image-118 " alt="Media reaction to Laterndl, 1940″ src=”https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/media-reaction-to-laterndl-1940.jpg?w=219″ width=”219″ height=”300″> Media reaction to Unterwegs, republished in Laterndl advert 1940The Laterndl’s first production was considered a great success and the company went on to perform it to full houses almost 60 times between June and August. However, these activities were curtailed by the outbreak of the Second World War in September, when all theatres and places of public entertainment were forced to close because of the potential danger from air raids. Even in the relative safety of London, the refugees’ activities were shaped by the actions of the regime from which they had escaped.

Footnotes

1 Franz Bönsch, ‘Das österreichische Exiltheater ‘Laterndl’ in London’, in Österreicher im Exil 1934 bis 1945: Protokoll des internationalen Symposiums zur Erforschung des österreichischen Exils von 1934 bis 1945, abgehalten vom 3. bis 6. Juni 1975 in Wien, ed. by Helene Maimann and Heinz Linzer (Vienna: Dokumentationsarchiv des Österreichischen Widerstandes und Dokumentationsstelle für Neuere Österreichische Literatur, 1977), pp. 441-450, (p. 441).

2 Richard Dove, ‘Acting for Austria: the Laterndl and other Austrian theatre groups’, in Out of Austria: the Austrian Centre in London in World War II, ed. by Marietta Bearman and others (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2008), pp. 113-140, (p. 114).

3 Dove, p. 114.

![Map of Czechoslovakia and northern Austria 1928-1938. Created by PANONIAN [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/map-czechoslovakia-and-austria-1935.png?w=300&h=136)

![Marie Geistinger and Alexander Girardi, painting 1894, Stadtchronik Wien, Verlag Christian Brandstädter [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/512px-girardi-geistinger.jpg?w=186&h=240)

![Oscar Homolka & Danielle De Metz in the US television series <em>Alfred Hitchcock Presents</em> - publicity still, 1960. By unknown (Revue Studios) (eBay) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/256px-oskar_homolka-danielle_de_metz_in_alfred_hitchcock_presents.jpg?w=192&h=240)

![Kurtheater in Reichenau an der Rax (Niederösterreich),2011. By Photo by Ferdinand Reichen. Architecture: Freedom of panorama (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0-at (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/at/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://norbertmiller.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/reichenau_an_der_rax_kurtheater1.jpg?w=300&h=176)